Program on Science, Technology and Society at HarvardHarvard Kennedy School of Government | Harvard University |

||||||||

|

|

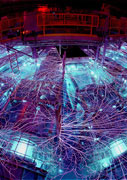

Workshops and PanelsSociotechnical Imaginaries: Cross-National Comparisons This two-day workshop at Harvard provided a chance for STS researchers to dedicated significant effort to developing sociotechnical imaginaries as a concept. November 14 (Friday)Session I:Consuming Biotechnology—of Rice, Pharma, and Risk This paper will analyze the double helix of state and market in formations of Chinese biotechnology over the past decade. In 2002, scientists from the Beijing Genomics Institute surprised the world scientific community by publishing the Indica rice genome sequence. Large scale production of genetically modified (GM) rice may soon join GM cotton (while GM soy is imported from the U.S.) despite concerns for GM rice products already present in Europe. The projections of China as a major pharma producer and scientific force in the 21st century are juxtaposed against a backdrop of extensive concern for tainted food or fake medicines. Governance of contamination such as melamine laced pet food, diethylene glycol infused toothpaste, or unregulated heparin production entails complex tracking of local production and global commodity chains. National stories of endangerment, vulnerability, and concerns for purity in food and drugs reflect ongoing reframings of citizenship and increased risk from consumption. With rising fuel and food costs as well as increased riots, the politics of consumption will be examined in relation to the imaginaries of biotechnology. Imaginaries Of and By the Nation-State: Corporate Biotechnologies in India and the Philippines Multi-national corporations are important actors in the global production of new biotechnologies for rice. This paper asks how multi-national corporations conceptualize national uptake of the genetic knowledge and genetically modified rice plants that they develop. Additionally, how do those countries that might utilize this knowledge or produce new genetically modified plants imagine the reception of these corporately-sponsored projects and engage with the corporations themselves? How are the relevant publics imagined within different national contexts in the discourse and development process? I will address these questions along three comparative dimensions. First, I focus on two different rice-related biotechnology projects—sequencing the rice genome and creating genetically engineered vitamin-A enriched golden rice. Second, I compare the work of two multi-national corporations—Monsanto and Syngenta—both of which have sequenced the rice genome and participated in developing golden rice. Finally, I analyze the corporate and national imaginary in two different countries, India and the Philippines. Logic, Ideology, Strategy, Epistemology: Keywords for an Analysis of Pharmaceutical Economies Understanding the global pharmaceutical economy is bewildering enough at an empirical level, even before we attend to the question of theorizing or conceptualizing it. Part of the challenge of conceptualization concerns the development of an analytic vocabulary that is adequate to precisely differentiate the various empirical phenomena that we set out to make sense of. (I think here of conversations around concept work that Rabinow, Lakoff and Collier have had through their ARC collaboratory). In this paper, I attempt to think with and beyond “imaginary” as one such concept by working closely through four concepts that I have used at various points in my work—logic, ideology, strategy, and epistemology. None of these are “my” terms; all of them have a rich philosophical lineage, especially in Marxian and / or Foucauldian intellectual genealogies. But I wish to consider the work they might do, and the calibrations required of these concepts, in the context of the emergent forms of life and value that global pharmaceutical economies present to us. The empirical material that I will draw upon is based on my ongoing fieldwork, which traces the interconnections between: i. The outsourcing of global clinical trials to India, and the concomitant infrastructure building in India to attract these trials; ii. Emergent epistemologies of biomedical research that bridge the gap between academe and industry, as well as lab and clinic (what is known as translational research); and iii. Disputes around the interpretation of post-WTO intellectual property regimes in the Indian context. What the larger project seeks to do empirically, then, is to look at the articulations between clinical research, biomedical epistemology and property regimes, in a historical conjuncture that is marked simultaneously by attempts at global commensuration on the one hand, and the emergence of particular national legal and political trajectories on the other. I wish to explore how we might think about the actions of corporations, nation-states and global civil society actors as they shape and get shaped by law, capital and technoscience at such an emergent conjuncture. Session II:Asian Regeneration?: Stem Cell Research in South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand This paper compares and contrasts characteristic stem cell research and regenerative medicine facilities in three Asian countries. While there is no unified “Asian biotech” in evidence—each country’s pattern is in stark contrast to the other two—there are continuities between the patterns in evidence and previous waves of Asian innovation and the national and intra-regional and international histories in question. The paper begins by describing disgraced scientist Hwang Woo Suk’s former work and lab facilities at Seoul National University as an example of biotech nationalism. The paper then discusses Singapore’s scientific personnel and real estate internationalism and Singapore’s investment in regulated but permissive basic stem cell research at its Biopolis facilities. Third, the paper describes medical and research facilities in Thailand, exploring emerging transnational networks of regenerative medical tourism. The axes of comparison include a focus on differences between: characteristic facilities; scientific strategies and specializations and hoped for pay-offs; the use of humans and animals; endorsed and de facto migrations and tourisms; economic investment and rationales; and emotional, familial, and nationalist, and transnational imaginaries. In sum, the paper explores the question of what each nation’s investment in this part of the biotech revolution tells us about the nation in question, as well as what these nation’s engagements with regenerative medicine adds to our understanding of biotechnology and its significance in a globalizing world. Securing the Future or a Threat to Democracy?: Stem Cell Research Policy Debates in South Korea This paper examines how the formulation of South Korea’s stem cell research policy, and the debates surrounding it, have been shaped by a contest over broader national sociotechnical imaginaries—that is, collectively imagined forms of life and order through which the nation state conceives and practices its sociotechnical relations. While stem cell research has been enthusiastically supported in South Korea, its significance has been understood and articulated somewhat differently than it has been elsewhere. Behind enthusiasm is public yearning for the development and protection of world-class “indigenous technologies” which would secure the techno-economic future of the Korean nation against foreign competitors. Though promises of future health benefits (e.g., curing degenerative diseases) have also played some role in fostering South Korea’s broad-based support for stem cell research, they have largely been interpreted through similar national aspirations (e.g., developing the world-leading cell therapy industry). The South Korean government’s decision to actively promote stem cell research has developed out of this cultural context and has been framed as a key step to the development of new biomedical industries—one of the nation’s ten strategic “next- generation growth-engine industries.” The government’s policy has not gone uncontested, however. Long before the infamous Hwang Woo-Suk scandal broke out, a group of progressive activists—including environmentalists, feminists, and public health advocates—began to strongly criticize the government’s handling of stem cell research. These activists were pro-reproductive rights and did not have a firm stance on the moral status of human embryos. But for them, the government’s seemingly unquestioning support for stem cell research embodied the “growth-first” ideology that they and their predecessors have fought hard against. Likewise, a pro-development alliance between science, technology, the state, and business—which the proponents of stem cell research deemed necessary to ensure the future and survival of the Korean nation— was seen as a threat to civil society, having the potential to subjugate justice and democracy to the so-called “national interests.” By situating South Korea’s stem cell research policy debates within this larger struggle over sociotechnical imaginaries, I will attempt to provide insight into the ways in which the meanings, purposes, and priorities of biomedical R& D are coproduced with South Korea’s distinctive yet contested ideas of public good, citizenship, and national identity. Imagining the Past, Present, and Future in Japanese Biotechnology I write about narratives of justification and narratives of nature that come from different constituencies, histories, nations—all spoken through the voices of Japanese scientists involved in genomics, bioinformatics, and systems biology. These narratives differ amongst Japanese scientists. Some are framed in distinctively Japanese culturalist terms, others as ‘scientific’ in the terms of notions of western/modern science, others in the language of posthuman, postmodern sciences. Further, as they are all in conversation, and oftentimes competition, with each other, their narratives are also deeply intertwined with each other and embedded in other narratives in place and time. Diversity within these narratives is my major focus. A second focus of this paper is the transnational production of science and technology, as embodied in these scientists; in current transformations in “the Japanese laboratory,” where students and researchers from around the world work; and in international collaborations. A third focus centers around the question: what it is the nation-state in a transnational scientific world? While some of these narratives are spoken and written to funding agencies and other policy oriented committees within “the Japanese government” (itself a diverse set of parties and narratives), this paper focuses less on state actors. Session III:Guerilla Engineers: The Internet and the Politics of Freedom in Indonesia This paper examines the construction of a sociotechnical imaginary for the Indonesian Internet during the 1990s and early-2000s. The advent of the Internet in Indonesia was a highly ideological affair in which many engineers and innovators sought to establish the Internet as a space of “freedom” from state control. Some Indonesian engineers talked of using “guerilla” tactics to “liberate” wireless bandwidths so as to allow for the creation of “community” networks. The idea that the Internet should be a communicative space for an open and free society, independent of state power, is certainly not particular to Indonesia. However, an examination of the history of the Internet in Indonesia reveals that the construction of this sociotechnical imaginary there should not be taken for granted. ‘Late’ Industrialization and Visions of Social Justice in Indonesia In 1950, the leaders of the Republic of Indonesia faced profound internal conflicts over political ideology and religion, the new government struggled to establish a shared ideological foundation on which to build. One element of that foundation was the belief that most poverty in Indonesia was a direct result of the Dutch domination of the economy during the colonial era. Both successful leaders and aspirants alike justified their claims to authority on the basis that they could produce a just and equitable system that facilitated prosperity. Sukarno enshrined this ideal of “social justice” in the Pancasila, the five principles of Indonesian government. The Politics of Skill At what levels are technoscience and power coproduced? The predominant analyses tend to focus on large institutions: states, NGOs, and international organizations. Yet as Sheila Jasanoff has written in States of Knowledge, “At whichever scale individual studies are framed, though, the findings help to clarify how power originates, where it gets lodged, who wields it, by what means, and with what effect within the complex networks of contemporary societies.” November 15 (Saturday)Session IV:Sociotechnical Imaginaries in Nanotechnology Assessment and Governance: Comparing Europe and the United States This article explores sociotechnical imaginaries related to nanotechnologies in different political cultures. It examines how the role of science and technology is imagined in the political cultures in Europe, especially Germany, and the United States. It looks at how the meanings and functions of science and its relation to society are shaped in policy documents aimed at deliberating future developments of nanotechnologies and defining national science policies and research strategies. The paper looks at the explicit goals and underlying assumptions that shape such deliberations and policies in different cultures. By analyzing the recent “action plans” of Germany and the EU, and the U.S. “NNI strategic plan”, which are all crucial documents in the current (supra-)national nanotechnology policies, the paper shows how science and technology and their relation to society are imagined differently in the respective political cultures. Discretionary Predictions: A Democratic Analysis of UK Nanotechnology Policy In the period since the late 1990s the UK embarked on a series of institutional innovations intended to rebuild public trust in the government’s handling of science and technology. Crises over BSE and the commercialisation of GM crops challenged established patterns in science policy leading to a broadening of the expertise brought into policy making, a move to greater transparency, and efforts to ‘engage the public’. At the same time nanotechnology was becoming recognised as a potentially significant area of research. By 2003 nanotechnology was taken by the UK government as an example of the new dispensation between science, the state and citizens. What Does It Mean to Address Imagined Publics in Contemporary Techno-sciences? A UK-based Review Science and Technology Studies has in recent years developed some productive perspectives for thinking about science and its publics under two dominant and linked conditions: of globalisation, and commercialisation. These remain as-yet quite underdeveloped. For example, the dominant liberal tradition of imagining ‘publics’ as composed of already-formed individual subjects with completed values and preferences, which come into conflict to varying degrees with the forms of social intervention generated by techno-scientific innovation trajectories, has given way to sociology of scientific knowledge insights which identify publics and subjects already being imagined in techno-scientific work, prior to any material impacts thereof. These processes can be identified in the three case-study domains of the Harvard NSF project—stem-cells, nuclear energy, and nanotechnologies (inter alia). Session V:Envisioning Information Technology in Rwanda Most East African countries lack adequate access to technologies such as computers, the Internet, fixed and mobile telephone lines and other communications technologies (ICT). At the levels of both international and national governance, significant resources are being directed to the formulation of ICT policy in Africa. Big Science Projects as Thought Experiments in Global Civil Society Big science research facilities usually have been in the planning and design stage about 25 years before they are constructed and ready to use. As one device is funded, competing plans for the next one proliferate. Gradually a consensus emerges in the relevant research community around one plan, and national academies are urged to place the facilities on priority lists for government funding of the design process. It might take another ten years of designing while enough commitment and funding is gathered for construction to begin. Politics and the Technological Imaginary – A Case Study from Gujarat This paper is not an attempt to look at imaginaries at a Nation State level because currently these imaginaries despite the idea of the Indian century are weak. The real ethnographic power emerges when we look at them at the level of the state, where each state embodies as it were a variant of the nationalist imaginary. This paper looks at Gujarat over the last few decades and explores how the use of technological and scientific imaginaries have allowed it to make transitions and legitimize them. The article focuses on the current post riot period when Gujarat has become the site of the Nano car. The paper argues that this phenomena cannot be understood without examining how the Chief Minister Narendra Modi uses technological imaginaries to play out his politics. The paper ranges over four periods beginning with Gujarat as a Gandhian and a textile imagination. It shows how every time the city reworks itself even through riots, it does so through the use of technological metaphors. Using the city as a site, it shows how Narendra Modi played with the idea of the consumer city, the science city, the new middle class city with the car as an embodiment. In fact, technological imaginaries are used to build and erase social memories. The paper discusses in particular how one road the SG Highway captures the future imagination of Gujarat as the epitome of a technological dream. Such an analysis challenges the current interpretations on purely communalist lines and shows how technological imaginaries make Modi a more lethal politician. Session VI:U.S. Technological Leadership and the Shaping of Postwar Europe As Europe emerged from the ruins of World War II, and the geopolitical fractures of the Cold War were put in place, policymakers in the United States imagined a future for the old continent that was modeled on a vision of their own society and gradually implemented by the leaven of American leadership. The peripheral ‘other’ was linked to the imperial center by ties of blood and history. Fractions of indigenous elites were essential nodes for the co-production of a regime of order that was put in place to secure markets and to defend the free world from the communist threat. Science and technology, now crucial to the power of the modern state, were enrolled in this transformative project. During the 1950s and 1960s they provided the United States with instruments to mold institutions that cohered with Washington’s dream of establishing a ‘United States of Europe’ under American leadership. This paper will show how policymakers sought to instrumentalize American scientific and technological prowess in two key sectors, the nuclear and space, to selectively strengthen collaborative organizations in continental Europe. Supranational politically, civilian in ambition, transparent organizationally and industrially, these organizations would be ‘legible’, accessible to Washington’s panoptic gaze and open to American influence. They would also divert scarce resources away from military programs, above all in France, where increasingly strident demands for national sovereignty threatened the Cold War regime of order imagined by Washington as it struggled to stabilize the world system. Globalist Imaginations of World Order: 1945-Present The second half of the 20th century saw the rise of distinctively global imaginaries—imaginaries that presumed that a growing array of societal problems could be understood, assessed, and managed on scales no smaller than the planet itself. In turn, these imaginaries—often driven by and encompassing of science and technology—have contributed to rising demands for the pursuit and institutionalization of global governance. In this essay, I explore the origins and shape of globalist imaginaries in the postwar era, their institutionalization in the United Nations Specialized Agencies, and their implications for emerging forms of transnational authority and governmentality. I also explore the implications of comparative sensibilities for a thoroughgoing understanding of the rise of globalism in world affairs. Two Regimes of Global Health This paper will analyze two contemporary regimes for envisioning and intervening in the field of global health: global health security and medical humanitarianism. Each of these regimes combines ethical-political and techno-scientific elements to provide a rationale for managing infectious disease on a global scale. However, they rest on very different visions both of the most salient health problems to work on and of the most appropriate means of approaching these problems. Global health security focuses on “emerging infections”—both natural and man-made—which typically emerge from the developing world and threaten the developed world. Exemplary diseases include SARS, avian influenza, and Ebola. Its problematic is one of preparedness for potentially catastrophic disease emergence—and thus key technoscientific interventions include developing real-time global disease surveillance capacities and rapid, flexible medical counter-measure production. This regime seeks to generate linkages between multilateral agencies such as WHO, OIE and FAO, national disease control agencies, and elements of local public health infrastructure such as diagnostic laboratories. Medical humanitarianism, on the other hand, focuses on diseases that already afflict the developing world, such as malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Its problematic is one of saving lives by providing access to existing interventions such as medication or bed nets, or through funding scientific research into new treatments or vaccines. In contrast to global health security, medical humanitarianism tends to develop “apolitical” connections—between global philanthropies, NGOs, scientific researchers (both in academia and in the private sector) and local public health workers. The type of ethical responsibility implied by a project of global health depends upon the regime in which the question is posed: the connection between health advocates and the afflicted can be one of either shared risk or of moral obligation to the other. The paper will explore the dynamics of these regimes through three examples: avian flu preparedness measures, malaria vaccine development, and the recent case of an airline passenger diagnosed with XDR-TB. Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Politics of Science and Technology: Cross-Cultural Comparisons In 2009, many of the researchers involved with the NSF project reconvened at the Society for the Social Studies of Science (4S) Annual Meeting held in Washington, DC. In this panel session, four papers were given that covered a broad range of topics: technoscientific imaginaries in Austria; Anglo-Chinese imaginaries in relation to agricultural biotechnology; embryo research and imagined public reason; and how an imaginaries lens might shed new light on the role of science and technology in South Korean national development. You may read the abstracts below, as well as slides from the discussant’s remarks. PanelChair: Sheila Jasanoff (Harvard University) Discussant: Regula Valérie Burri (ETH & University of Zurich) Slides available here Assembling, Rehearsing and Stabilising: Technoscentific Imaginaries, Societal Models and “Austrian Futures” Over the past years national (and European) science policy as well as media discourses on technoscientific innovation have been key-agents in the production of certain kinds of societal futures. At the same time such potential futures are always closely intertwined with the assessment of the future potential of new technoscientific developments. These technoscientific futures as well as the orders embedded in them find their expression in a rich repertoire of promises and imaginaries narrated along with the technoscientific accomplishments expected to realize them. How these imaginaries are made local and thus recognisable, which promises seem reasonable and credible in a specific context and why, but also who are legitimate architects of these “Austrian technoscientific futures” will be key questions. To contribute to an understanding of how technoscientific imaginaries, models of society and locally compatible futures are assembled into seemingly coherent narratives, how and where these are then rehearsed and how some of them in the end manage to get stabilised (naturalised) in a specific national context, i.e. Austria, is thus the aim of this paper. The paper will use selected policy and media material from two scientific fields—genetics/genomics and nanotechnologies—collected in the framework of two recent research projects (Living Changes in the Life Sciences, ELSA/GENAU; Making Futures Present: On the Co-Production of Nano and Society, FWF). The material covers in particular the last decade. Both fields were established through extensive national research programmes and are staged as key-agents in national innovation policy and thus for economic and more broadly societal development. The analysis will draw attention to the technoscientific imaginaries exposed, will investigate the ways in which a specifically “Austrian societal model” gets performed and how this society is understood as ordered and will show what related potential futures are coproduced. Using a comparative gaze, the paper will look into important similarities and differences between these two technoscientific fields. Cosmopolitan Innovation Imaginaries? Comparative and Convergent Aspects of Anglo-Chinese Scientific Research Collaboration in Agricultural Biotechnologies Agricultural biotechnologies, including but not exclusive to the cluster of existing and imagined future GM trajectories, have been strongly linked to the increasingly powerful agenda of climate change adaptation, and even mitigation. For example, drought and salinity resistance have been promoted as powerful reasons to adopt GM agricultural technologies as responses to climate change. As a universal global problem albeit with very different local variations and consequences, and with GM as an imagined (and asserted) universal technology, it might appear at first sight that not too many comparative dimensions would be evident in this field. Despite large investments and expected products, GM innovation has stalled in this domain as the gene-organism-environmental complexities of this trait have gradually become evident to research that, building upon the existing single-gene technologies and traits like herbicide-resistance, was expected, and promised, to yield useful results earlier. Bayer Crop Science now claims to be on the verge of bringing a drought-resistant variety of GM maize to field-trial applications. Other non-GM drought-mitigating plant technologies are also being trialed in agricultural R&D large-scale field-tests in China and elsewhere, with UK collaboration. Cosmopolitan innovation as a concept encompasses technical, environmental and social-cultural dimensions, and this normatively weighted concept will first be explained in the paper. Secondly we will analyse the ways in which technical imaginaries of social conditions and practicalities (e.g. farm-conditions and practices, farmer capacities and attitudes; regulatory constraints; market conditions) influence technical commitments and imaginaries as to what is feasible, desirable, and priority, thus the research and innovation agenda. Finally we will examine the comparative differences of such technosocial imaginaries can be detected between typical UK or European scientists, and Chinese scientists, and how these may be interpreted as variances patterned along comparative cultural or social (including economic and political) dimensions. Even where little or no such comparative variance is evident, the further question arises as to how has convergence been achieved, and with what implications; for example, for the flexible design of agricultural technologies appropriate to very different operating conditions, across hugely different environmental, economic, social and cultural countries/regions. In this sense, “cosmopolitan innovation” could be seen as innovation which respects—and reflects—local differences, yet can practically address global issues with global welfare imagination and commitment. Imagining Public Reason in the Human Embryo Research Debates American debates over human embryo research have called into question the sorts of epistemic, normative and democratic arrangements sufficient to engender reasoned public discourse in American political culture. The public/private boundary has been central to American deliberations because policy questions have been largely confined to questions of public funding (and the regulation of publicly funded science), leaving aside questions of whether and how private sector research activities are regulated. As such, “the public” has referred to a multiplicity of heterogeneous elements, drawing them into association while at once demarcating them from the “private.” These elements have included discourse (both epistemic and normative), structures of scientific and technological innovation, institutions of democratic representation, goods (both moral and material), capital, etc. Thus the work of imagining the public—as a category of interests, as a collection of individuals, as a domain of normative deliberation—has been an essential feature of the debates from their inception. This paper will examine how one critical element of the “public” came to be a central focus of deliberation: the giving of public reasons. The paper contends that efforts to identify the types of reasons appropriate to public deliberation became a core locus for imagining the “public” more broadly, particularly between 1970s discussions of fetal research and the deliberations of the NIH Embryo Research Panel in the early 1990s. It further argues that assessments of reason-giving invoked, rearticulated and solidified broader imaginaries of the public and the place of science and technology within it. Finally, the paper demonstrates that the most persistent and consequential imaginaries of the public (and public reason) emerged not so much out of normative questions of democratic representation, but out of technical arguments over the accuracy of accounts of certain natural facts. Rethinking the Political Economy of Science, Technology, and National Development in South Korea: “Sociotechnical Imaginaries” Perspectives The literature on East Asian political economy repeatedly asserts that science and technology have played an important part in the rapid socioeconomic transformation of postcolonial South Korea. However, while some of its more recent findings challenge the conventional wisdom of neoclassical economics and modernization theory, the way it approaches science and technology remains largely traditional and context-insensitive. Attention is given to the active role of the state in promoting science and technology, to the unique patterns of technological learning and innovation at the level of firms, or to the ingenious efforts of scientists and engineers. Yet, the emphasis is predominantly on the impact and efficiency of these processes with respect to South Korea’s economic and industrial performance. The meanings, purposes, and content of science and technology, as well as the criteria for assessing their impact and efficiency, are taken as more or less given, rather than understood as products of particular social and historical contexts. STS can provide an antidote to this tendency, but the field’s focus on micro-level processes makes it difficult to link a contextual understanding of science and technology to broader social and political questions. The present paper argues that the notion of sociotechnical imaginaries (as defined in the panel abstract) can help remedy this problem by placing the co-production of science, technology, and socio-political order at the center of analysis. In particular, by drawing on three case studies of nuclear power, stem cell research, and nanotechnology, the paper illustrates the ways in which the imagination of the role and place of science and technology in society has embedded, and has been embedded in, the distinctive ideas of development, nationhood, and the state/citizenship in South Korea. Innovation in STS: Method and Scale in Sociotechnical Imaginaries In 2010, There was another reconvening of many researchers that the 4S Annual Meeting, this time in Tokyo. Over two panel sessions, some ideas from the previous years were re-worked and further developed, and new angles on sociotechincal imaginaries were outlined. You may read the abstracts below. First PanelChair & Discussant: Sheila Jasanoff (Harvard University) Imaginaries & Scale: Nanotechnology Governance in the United States Science governance is deeply shaped by specific imaginations of the science-society relationship. Jasanoff and Kim (2009) have pointed to “sociotechnical imaginaries” that are expressed in the ways political cultures imagine social order related to scientific or technological projects. Following this perspective, this paper explores imaginaries in science governance in a particular political culture. Taking nanotechnologies in the United States as an example, the paper reveals the imaginaries and sociopolitical assumptions that are related to these emerging technologies and are expressed by relevant stakeholders. By drawing on interviews with policymakers and scientists, it is interested in the ways scientific innovation and its regulation are envisioned by involved actors in the US context. More specifically, the paper inquires how nanotechnologies, their risks, and their future are envisioned, and how their political handling and public involvement is projected by US stakeholders. Building on such investigations and addressing the methodological question of scale, the paper asks how such visions and perceptions of individuals can be seen as expressions of more general (sociotechnical, cultural) imaginaries related to a political culture. Keeping Technologies Out: Absent Presences, Sociotechnical Imaginaries and National Identity Formation Over the past years contributions started to look at how technologies get inscribed into national political cultures and participate in the creation of what was labeled “sociotechnical imaginaries” (Jasanoff and Kim), thus in the establishment of imagined preferred forms of social life and social order organized around the development and implementation of technoscientific projects. This paper aims at taking a different turn and investigates what will be labeled “the sociotechnical imaginaries of the absent”. More concretely the paper will investigate how nuclear power and genetically modified organisms participated in the creating of sociotechnical imaginaries in the Austrian context and how that again was tied into wider ideas of national identity. Both nuclear power and GMOs have been “banned” from the Austrian context through complex technopolitical processes, thus making this absence present in multiple ways. Using John Law’s distinction, the paper thus addresses manifest technological absences, i.e. acknowledged and made explicit forms of absence, that have managed to occupy a space in the national context, to develop forms of materiality and to get woven into narratives that participate in the formation of sociotechnical imaginaries of a particular kind. The paper will first investigate the multi-sited processes through which these absences are made constantly present in order to keep the sociotechnical imaginaries alive. In a second move the question of how these “sociotechnical imaginaries of the absent” impact on upcoming new technologies such as nanotechnologies. H1N1 and the Sociotechnical Imaginary of Disease This talk describes what might be termed a global dispositif, or apparatus, for envisioning and intervening in potential disease outbreaks. The dispositif includes both social and technical elements: epidemiological methods for tracking disease incidence; global communication systems designed to transcend national reporting systems; diplomatic agreements to implement collective response mechanisms in the face of threatening events; and contracts with pharmaceutical companies specifying the production and distribution of medical countermeasures. It both responds to and helps to sustain a global sociotechnical imaginary of disease: one in which disease outbreaks – whether from naturally occurring pathogens, intentional bioattacks, or as side effects of technological development – continually threaten collective health and social order across national boundaries. The talk will focus empirically on the debate over the WHO’s declaration of H1N1 influenza as a pandemic – and the technical responses this declaration put in motion. It will ask: What is the collectivity that is brought into being through global disease tracking systems? And what populations are either included in – or excluded from – global systems of response? Imagining Control: International Efforts to Prevent Malicious Technology Diffusion A major shift began to occur in the imaginary that supported multilateral export controls efforts after the Cold War ended. For all of the history of export controls, they have always been about three goals: preventing foreign supply of a technology; ensuring domestic supply; or as a tool for foreign relations. International efforts, until 1996, focused solely on the first of these goals. All of them are based on an adversarial imaginary of “us versus them”. This is very different than the imaginary that has developed around new international efforts, most notable the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies. This new imaginary is collaborative, focused less on controlling who gets access to malicious technology and more on creating a global system that ensures that any such decision is made by a state and not an individual or company within that state. Each of these imaginaries has their basis in imaginaries developed within national export control systems; that is, some systems are based more on collaborative imaginaries and others more on adversarial imaginaries. In this paper, I analyze how these competing imaginaries are vying for the necessarily political will to reform the multilateral export control system so that it is more in line with their imagination. Sociotechnical Imaginaries and Global STS This paper reviews the legacy paradigms of sociotechnical imaginaries as they have been deployed as global scientific projects (e.g., the IGY or HGP), as national-building of scientific capacity (e.g., the LBA or Biopolis), as regional alliances (e.g. the ASEAN SNP consortium), and as “switching points” in new configurations of “republics of science” as re-imagined for public futures, requiring increased distributed, and local expertises (biodiversity policy conflicts, new translational medicine initiatives such as THISTI). Second PanelChair & Discussant: Ulrike Felt (University of Vienna) From the National to the Local: Scale and the Sociotechnical Imaginary of the Cooperative in Indonesia This talk explores the question of scale in the framework of the sociotechnical imaginary. Jasanoff and Kim have defined the sociotechnical imaginary as “collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfillment of nation-specific technological projects.” This paper examines how the sociotechnical imaginary might be used to illuminate the longer term significance, or afterlife, of abandoned national policies, a situation in which the movement from national to subnational actors and scope of action must be considered seriously. A crucial methodological challenge is how to analyze the shift from state actors operating on a national stage to independent, local actors who use the imaginary to inform projects of dramatically smaller scope long after the demise of the original policies. The story I will briefly examine is that of cooperatives in post-colonial Indonesia. The technological dimensions of this story have usually been overlooked, in part because both Sukarno and Suharto gave little more than lip service to the idea of the cooperative as a serious instrument of technological development. However, my research indicates that the project of cooperative development in Indonesia was powered by a clear sociotechnical imaginary, one that reappears among local activists in Suharto’s Indonesia and in post-authoritarian Indonesia. Aside from investigating how to trace the action of an imaginary in time under these conditions, I will inquire whether it is sensible to view the sociotechnical imaginary as an agent of continuity in the face of interrupted or defunct policies, and in the process consider the implications of the dramatic differences of the scale of operation of the imaginary for the shaping of the national technical and social order in Indonesia. Problematizing the “National” in National Sociotechnical Imaginaries: The Case of South Korea While science and technology are ubiquitously embraced by modern states as driving forces for progress and prosperity, their construction in any given context is almost always closely intertwined with a particular imagination of nationhood and national history. Science and technology are not just mobilized—materially and symbolically—in the (re)imagining of nations in the sense proposed by Benedict Anderson. As Jasanoff has repeatedly pointed out, the contents, meanings and purposes of science and technology, the public good they should deliver, and the roles and identities of the state, scientists and technologists, and publics are also all simultaneously (re)imagined (or co-produced) in that process. The notion of “sociotechnical imaginaries” can help us examine the ways in which these constellations emerge and become stabilized or contested, and compare how they vary from one country to another. On the other hand, the focus on “nationally specific” sociotechnical imaginaries may well divert attention away from the very idea that nation, or nation-state, is itself constructed and hybrid and requires hard socio-cultural, political and material work to be maintained. Ironically, this may in turn lead to an overemphasis on the translocal or transnational scalability of sociotechnical imaginaries. By using the selective episodes of South Korean controversies (e.g., debates on nuclear power, energy policy, and stem cell research), the present paper explores a more nuanced approach to “national” sociotechnical imaginaries (and their relations to the “nation-state”). South Korea’s unique imagination of the role and place of science and technology in society has embedded—and been embedded in—distinctive, collectively shared ideas of nationhood, the state, and development. The paper suggests, however, that while the resulting sociotechnical imaginaries are powerful at the level of nation and nation-state, their boundaries are often diffuse, fragmented, and contentious. China Biotech: on Governance, Risk, and Citizenship This paper explores ways in which the biosciences in contemporary China frame cultural beliefs and meanings of biosecurity. We will analyze the double helix of state and market in formations of Chinese biotechnology over the past decade to address questions of scale and methods of study. In 2002, scientists from the Beijing Genomics Institute surprised the world scientific community by publishing the Indica rice genome sequence. Large scale production of genetically modified (GM) rice may soon join GM cotton (while GM soy is imported from the U.S.) despite concerns for GM rice products already present in Europe. The projections of China as a major pharma producer and scientific force in the 21st century are juxtaposed against a backdrop of extensive concern for tainted food or fake medicines. Governance of contamination such as melamine laced pet food, diethylene glycol infused toothpaste, or unregulated heparin production entails complex tracking of local production and global commodity chains. National stories of endangerment, vulnerability, and concerns for purity in food and drugs reflect ongoing reframings of citizenship and increased risk from consumption. With rising fuel and food costs as well as increased riots, the politics of consumption will be examined in relation to the sociotechnical imaginaries of biotechnology. Performing Trust at the Fault Lines of Glocal Science Some STS work has assumed an agonistic field of interests while paradoxically neglecting power. Rational actor models abound in STS, even though they have been undermined in many fields for decades. When I tell scientists that some STSers claim trust is unimportant in large, well-organized collaborations: the response is always laughter. Since the 1970s social and biological scientists have examined altruism and the study of commons has intensified in law, history, anthropology, and other fields; meanwhile, many have studied ethical practices in various communities. This basic research on altruism, commons, and ethics is already being used to make policies. For many decades anthropologists have argued that naming, jokes, stories, and gossip [NJSG] are significant practices for understanding any group’s ethos. NJSG are intimately entwined with evaluating research styles, aesthetics of research design, and ambiguities in making knowledge. All these phenomena, including trustworthiness, are constituted, transmitted, debated, and revised via NJSG. Forms of NJSG shift with gender, generation, and locality, while access to NJSG is restricted in multiple ways. NJSG practices are a crucial part of any community of shared practices Size matters: costs escalate for the new infrastructures; distributed research communities are imploding as new kinds of global laboratories are being designed and constructed. Trust matters as trans-local clusters merge and morph. The multi-cultural strategic actors who are continuously negotiating a shape-shifting glocal consensus usually are men. I have argued that crucial negotiations occur at fault lines where different kinds of researchers come together to develop new strategies about what they come to see as new, shared problems, willing to redefine research and infrastructure. Those ruptures and gaps are filled with NJSG, building trust, commons, and new exclusions. In my talk I will discuss how to examine NJSG in such sites. |

|||||||