Program on Science, Technology and Society at HarvardHarvard Kennedy School of Government | Harvard University |

|||||||

|

|

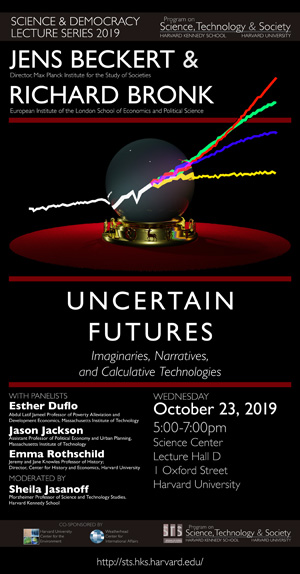

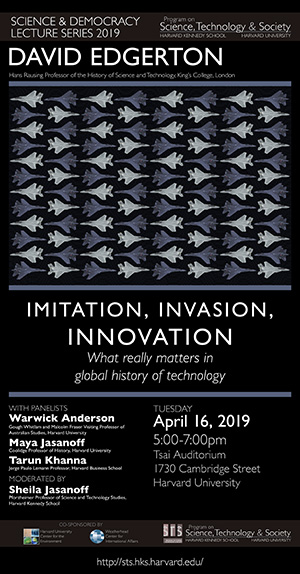

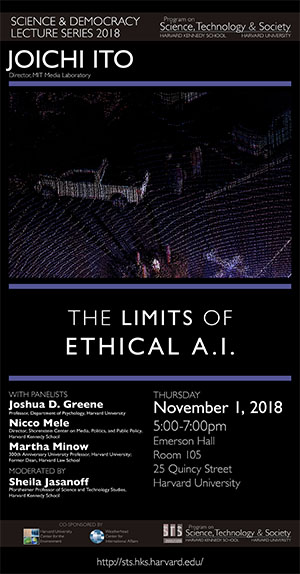

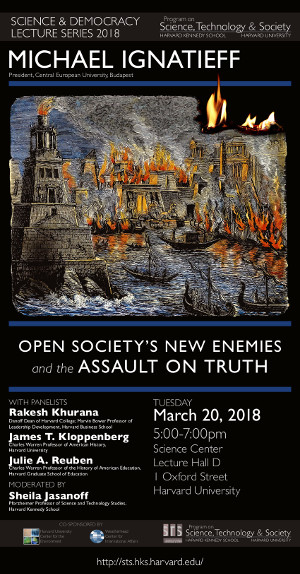

Science and Democracy Lecture SeriesOnce a semester, the STS Program, with co-sponsorship from other local institutions, hosts an installation in its Science and Democracy Lecture Series. The series aims to spark lively, university-wide discussion of the place and meaning of science and technology, broadly conceived, in democratic societies. We hope to explore both the promised benefits of our era’s most salient scientific and technological breakthroughs and the potentially harmful consequences of developments that are inadequately understood, debated, or managed by politicians, institutions, and lay publics. All lectures and panels are free and open to the public.  With the advent of the AI age, we face a constitutional crisis, not merely a regulatory vacuum. Private technology companies have evolved into "digital sovereigns"—entities that exercise quasi-governmental power over speech, commerce, and civic life without shouldering the constitutional obligations that bind governments. The First Amendment was designed to protect speakers from government censorship, but it says nothing about private algorithms that determine which voices get heard and which get buried. This structural "First Amendment mismatch" between eighteenth-century constitutional frameworks and twenty-first-century digital reality threatens democratic self-governance itself. Drawing on archival research, internal corporate documents, and interviews with industry leaders, the book traces how Section 230 created a governance framework beyond constitutional safeguards, examines how this misalignment has compromised privacy, autonomy, and integrity, and presents competing visions for our digital future—dominarchy or democratic renovation. Co-sponsored by Harvard University Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University Center for the Environment (A Center of the Salata Institute), and the McQuillan Institute.  This symposium introduces the work of the McQuillan Institute for Science, Technology and the Human Future through a collaboration with the Program on Science, Technology and Society (STS) at Harvard. The program highlights how STS scholarship, and research on science and technology more broadly, can inform some of the most important challenges currently facing human societies, from digital and climate governance to rethinking the role of technical expertise in law and democratic politics. We close with a reflection on reimagining the future of technological societies through conversations between artists and social scientists. Register and view the full program here.  In 2023 generative AI was thrust into the consumer space, signaling a new era. Looked at another way, it also triggered a vast parade of groundhog days. Surveillance capitalism’s antidemocratic original sins and its progress toward totalities of knowledge and power are repeated, upscaled, and driven further into everyday life. There is a genuine path out of this house of mirrors that leads through theory and politics-- comprehension, communication, and collective action. There is progress to build on. Will a new generation take up this challenge for the sake of a democratic information civilization? Co-sponsored by Harvard University Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University Center for the Environment (A Center of the Salata Institute), the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, and John and Elizabeth McQuillan.  These days, supported by large language learning programs, people are offered pretend empathy in chatbots that take the role of therapists, companions, and even lovers. But no matter how convincing, these programs can only provide simulations because they have not known the arc of human life. They cannot put themselves in our place. They feel nothing of the human loss, love, or trouble we describe to them. Or that they represent to us. Yet we are comforted by the simpler vision of the world that they provide. Human relations are rich, messy, and demanding. We clean them up with technology. We feel less vulnerable talking to programs than to people. Here, my focus is not on what generative AI can do, but on what this new category of intimate machine is doing to people and our social worlds. Co-sponsored by Harvard University Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University Center for the Environment (A Center of the Salata Institute), and John and Elizabeth McQuillan.  There is no historical precedent for a technology with as profound ramifications as artificial intelligence being developed with so few checks and balances. In an age typified by information overload and polarized politics, the relative absence of a public discourse around AI is striking. We have a profound democracy deficit in this area, with little progress in developing oversight mechanisms, transparency and regulation. The complexity of the technology and of the issues it raises should not defeat our ability to determine schemas for ensuring it meets our needs, and not the other way around. Equally, the public good needs to be asserted in a realm dominated by private sector actors with little accountability. Nowhere is this more true than in our cities which are about to be inundated with a host of AI-related challenges, from the safety concerns regarding self-driving vehicles to the massive loss of employment likely from AI-enabled automation. As has been true all over the globe on huge challenges like inequality, racism and climate, cities will have to be the problem-solvers and the innovators. We need a democratic methodology for addressing AI and we need it immediately. If we don’t answer the question “Who decides?,” then matters will surely be decided about us, without us. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs and John and Elizabeth McQuillan  Democracy is famously described, in Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, as "government of the people, by the people and for the people." But how can leaders and policy makers know that the decisions they make are in the best interests of the people? Science is the only tool that humankind as devised for reliably peering into the future to determine how the laws of natural and human nature will play out under different policy and management options. It is not the role of science to prescribe what the policies should be, as there are factors other than science that must be weighed by leaders in any decision. However, by predicting what outcomes will ensue under different options, members of the public and others can ask: “Is this outcome compatible with our values?” The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) was established by Abraham Lincoln to provide science-based advice to better inform decisions on national security and the wellbeing of American citizens. In the more than 150 years since its founding, the NAS has weighed in on the challenges of the times, and we have emerged stronger thanks to this advice. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  Lecture Description: The lecture will present White House Office of Science and Technology Policy efforts to create a new roadmap for science and society that reflects democratic values, advances equity, and upholds scientific integrity. Deputy Director Alondra Nelson will broach a wide range of topics, including equitable data, upholding rights in an increasingly automated society, the White House Scientific Integrity Task Force, and more. A crosscutting theme of the lecture is how science and technology policymakers in the Biden-Harris Administration are working to restore trust in government, advance equity at scale, and fortify democratic values. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, and the Harvard Data Science Initiative.  Internet pioneers expected freedom and the wisdom of crowds, not that we would all be under the thumb of giant corporations profiting from a market in disinformation. We can still recover, but at least so far, Silicon Valley appears to be part of the problem more than it is part of the solution. Can we master the demons of our own design? The governance of AI is no simple task. It means rethinking deeply how we govern our companies, our markets and our society—not just managing a stand-alone new technology. It will be unbelievably hard—one of the greatest challenges of the twenty-first century—but it is also a tremendous opportunity. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  The word ‘crisis’ has two different shades of meaning. It can refer to an unstable situation in political or social affairs that persists and intensifies over the relatively long term. Closer to the original Greek meaning of krisis, a crisis also refers to a traumatic episode or condition whose resolution remains unclear and replete with danger. The crisis of democratic leadership is a crisis of the first sort — a slow burn tending towards meltdown. The coronavirus pandemic is a crisis of the second sort — a traumatic event spiralling into an uncertain and perilous future. The crisis of the first sort is currently feeding into and feeding off the crisis of the second sort. COVID-19 has had an extraordinary effect on the political landscape. Its challenge to democratic leadership and to the paradigm of representative democracy more generally may be framed according to a number of key features. First, the pandemic may be considered as a premonitory event. Secondly, it poses various acute problems of collective action, both within and beyond the polity. Thirdly, it highlights the dense interconnectedness of the issues that form our political agenda. And fourthly, it suspends many aspects of social and political life, both pausing our capacity to act and interrupting the flow of the world we act upon. Each of these features has double-edged implications for our capacity to steer our democracies. Each threatens to reinforce democratic impotence, but at the margins each also offers some hope of democratic renewal. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  Dynamic capitalist economies are characterised by relentless innovation and novelty and hence exhibit an indeterminacy that cannot be reduced to measurable risk. How then do economic actors form expectations and decide how to act despite this uncertainty? This talk will focus on the role played by imaginaries, narratives, and calculative technologies, and argue that the market impact of shared calculation devices, social narratives, and contingent imaginaries underlines the rationale for a new form of ‘narrative economics’ and a theory of fictional (rather than rational) expectations. When expectations cannot be anchored in objective probability functions, the future belongs to those with the market, political, or rhetorical power to make their models or stories count. The talk will also explore the dangers of analytical monocultures and discourses of best practice in conditions of uncertainty, as well as the link between uncertainty and some aspects of populism such as the distrust of experts. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  In the last twenty or thirty years innovation has been central to the discourse on the economy. This ‘innovation’ is disruptive, pervasive and fast, demanding new economic, political and social forms. On the other hand, the world has seen unprecedented rates of imitation, not least of old forms. In our imaginations innovation and imitation occupy different geographical, economic and moral spaces. Innovation is seen positively and futuristically, as a feature of a few selected, creative, entrepreneurial places; it marches with time. Imitation is seen in more hard-headed, economic ways; as a feature of developing countries, as a sign of imaginative inadequacy, and lack of authenticity; it moves with incomes not time. Breaking down these oppositions and taking imitation seriously is the key to understanding global technical change in the twentieth century. Video available here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  Public discourse on the ethics and governance of AI is increasingly dominated by a particular vision of the solutions: the promotion of voluntary "responsible practices" over enforceable regulations; the reduction of complex epistemological concerns to questions of "bias"; the attempt to settle political disputes with algorithmic formalisms of "fairness." The talk will examine the limits and implications of this vision, and offer an alternative formulation of the key challenges. Video available here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  As a philosopher of science, Karl Popper was unique, among 20th century political thinkers, in the emphasis he placed upon scientific knowledge as a precondition for political freedom in a democratic society. Openness was, above all, a moral and intellectual commitment to falsification and to constant self-correction and self-criticism. The 21st century’s ‘new enemies’ of open society—ideological nationalism and authoritarian populism, empowered by new technologies—pose a challenge to Popper’s epistemological ideal of a free society and ask us to think again about ‘the marketplace of ideas’ model of democratic debate. The lecture responds to these challenges by exploring how to restore the authority of scientific knowledge in public debate. Video available here.

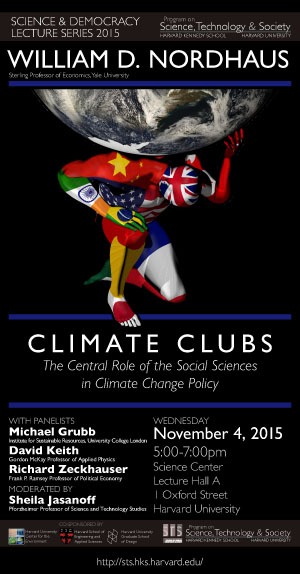

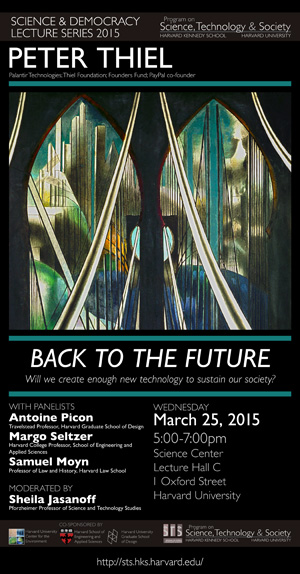

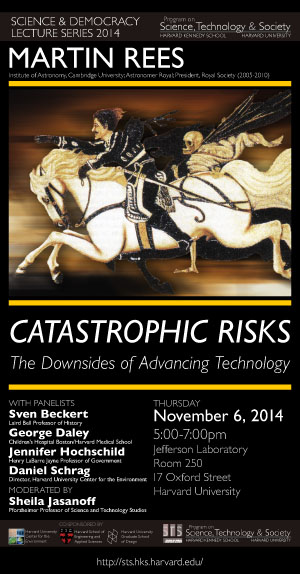

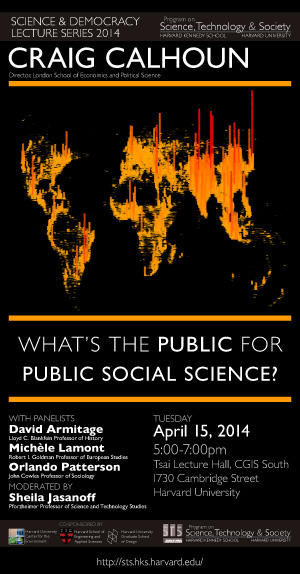

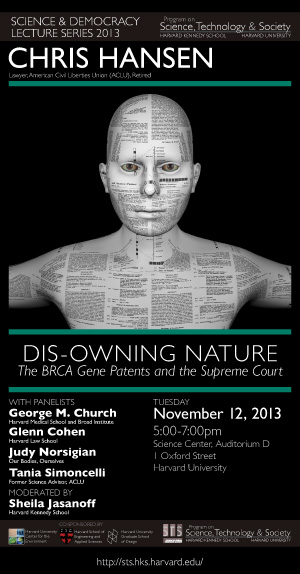

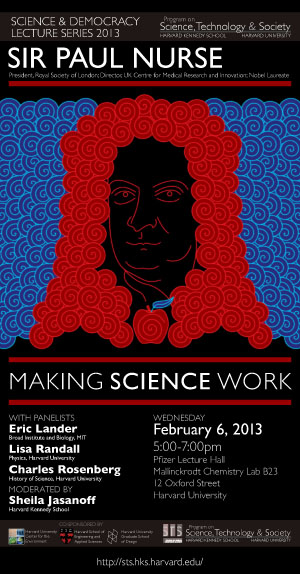

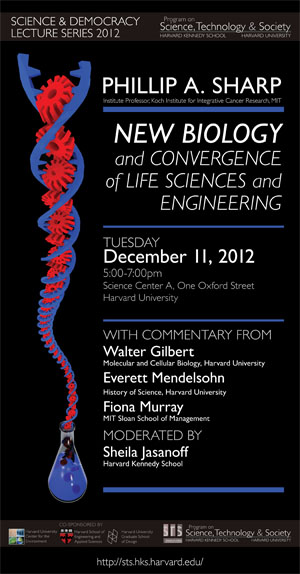

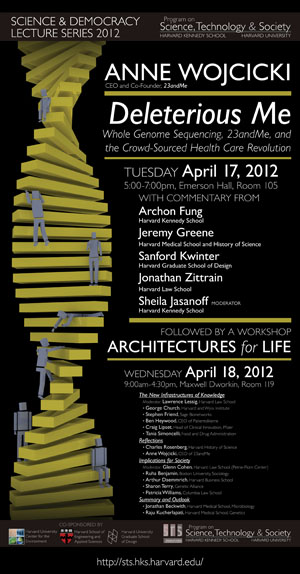

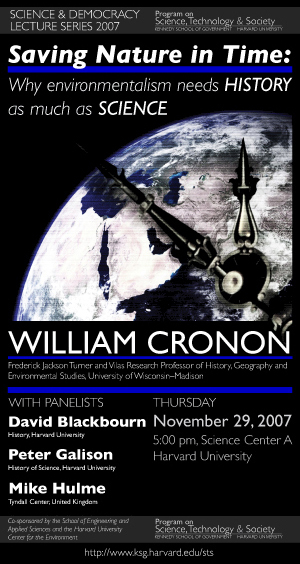

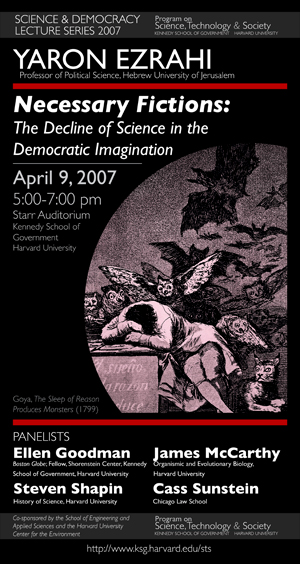

Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  The Indian environmental stories that are making international headlines are the ghastly air pollution and the nation's inability to control filth, garbage and sewage that are overwhelming its cities, rivers and fields. The other narrative linking India to the rest of the world is that India is the major villain in climate change. I ask, can India can beat the pollution game by following the trajectory of the western world? Won't capital and resource-intensive methods of environmental management simply add to the burden of inequality, and so to unsustainability? Also, is India the villain or the victim in international climate politics? Are there lessons in India for the global community in its fight against climate change? I will discuss how democracy and dissent must work together so that the environmentalism of the poor dictates the politics of change. Not just change in India, but change in the world. Video available here. Read a summary of the next day's public conversation with Sunita Narain here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.  Over a year ago, Carlos Moedas, EU Commissioner for Science and Innovation, launched SAM - the Scientific Advice Mechanism, a new model to incorporate in a structured way the inputs of the scientific community in the decisions taken by the European Commission. In this talk, Mr. Moedas will address the rising importance of scientific advice in policy making, the need to build partnerships of trust between scientists and politicians, and the vital place of science in our contentious political environment. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.  Last year, world leaders agreed to put their nations on a pathway to “well below 2°C” of global warming in order to meet the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). One of those goals – SDG #7 – calls for countries to secure affordable and clean energy for the 1.3 billion people still living in energy poverty by 2030. Now, an array of grassroots organizations are pushing leaders to adopt an "energy efficiency first" approach, putting access at the center of their energy plans. This approach calls for distributed energy solutions to help countries go further, faster toward closing the energy access gap. Kyte will discuss how the work of these organizations can accelerate the national energy plans that countries around the world are currently putting into action. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.  Democratic societies are caught up in unprecedented political upheavals that are questioning some long-established principles of representative government. Do political parties matter? Are compromise and civility necessary for governing well? Do interests and identities take precedence over other bases for solidarity, including the ties of nationhood? All four countries represented on this panel—US, UK, Israel, India—are confronting these challenges in unique ways. In each, new digital technologies are centrally implicated in turning conventional democratic processes on their heads. Our discussion will be led by four of the most provocative and knowledgeable voices contributing to democratic theory today, all with specific insights into the realignment of politics and political subjectivities in the digital age. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  Much progress has been made by scientists and economists in understanding the science, technologies, and policies involved in climate change and reducing emissions. Notwithstanding this progress, it has up to now proven difficult to induce countries to join in an international agreement with significant reductions in emissions. The talk suggests that the Kyoto Protocol ran aground because of the tendency of countries to free-ride on the efforts of others for global public goods. It discusses how this tendency is rooted in international law, and examines the ways that nations have overcome free-riding in other areas. The article examines the “club model” as a mechanism to provide public goods and overcome free-riding. It examines the idea of a Climate Club and suggests that current approaches, starting with the Kyoto Protocol and continuing with the upcoming Paris meeting, have little chance of success unless they adopt some of the strategies associated with the club model of international agreements. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  Recent discussions about the role of technology in society have oscillated between very short term worries ("what are smart phones doing to our brains?") and very long term nightmares ("will artificial intelligence replace humanity?"). Left out of these discussions are the next twenty years: our horizon for making concrete plans. The most important question for this medium term might be: will we create enough new technology to sustain our society? Instead of taking it for granted (or doomed), we must go back to the future and build it ourselves. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  Our Earth is 45 million centuries old. But this century is the first when one species ours can determine the biosphere's fate. Threats from the collective "footprint" of 9 billion people seeking food, resources and energy are widely discussed. But less well studied is the potential vulnerability of our globally-linked society to the unintended consequences of powerful technologies not only nuclear, but (even more) biotech, advanced AI, geo-engineering and so forth. These are advancing fast, and bring with them great hopes, but also great fears. They will present new threats more diverse and more intractable than nuclear weapons have done. More expertise is needed to assess which long-term threats are credible, versus which will stay science fiction, and to explore how to enhance resilience against the more credible ones. We need to formulate guidelines that achieve optimal balance between precautionary policies, and the benign exploitation of new technologies. We shouldn't be complacent that the probabilities of catastrophe are miniscule. Humans have survived for millennia, despite storms, earthquakes, and pestilence. But we have zero grounds for confidence that we can survive the worst that the future can bring. It's an important maxim that "the unfamiliar is not the same as the improbable. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  In the last few years, almost every social science discipline has launched efforts to be more "public" in its work. Some of these are framed mainly in terms of communication of research results; others aim to build communication and an orientation to public purposes into every stage of the research process. In most of these efforts, though, the idea of 'public' has itself been underspecified. And at the same time, there have been substantial changes in the public sphere that have challenged older ideas about how academic knowledge might inform public debate or public policy. In this talk I take up questions about changing media, national and transnational arenas, and the extent to which academia is itself a public sphere. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  The discovery of new scientific knowledge and the application of scientific knowledge, are sometimes presented as being very different from each other. The fact is, however, that scientific enquiry has always been concerned both with acquiring knowledge of the natural world and of ourselves, and with using that knowledge for the public good. But science should not be judged solely in a utilitarian manner. Making science work for human benefit requires making good decisions about what scientific research should be supported and giving good scientific advice for public policy. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  Revolutionary advances over the past half century produced the sequence of the human genome and remarkable advances in the understanding of disease. Perhaps more important, the technology of DNA sequencing has revealed the information of all life forms. This advance can be considered the second revolution in life sciences, the first being the discovery of the structure of DNA. The third revolution will come from the convergence of life sciences with engineering, and computation and physical sciences. Convergence will help mankind meet some of the major challenges of the coming century, i.e. food for nine billion people, better protection of the environment, sustainable energy sources and better quality of healthcare. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.  In this talk, Morris will reflect on his experiences researching and producing four of his most celebrated films — "The Thin Blue Line", on a Texas murder case; "Mr. Death", on capital punishment and Holocaust denial; "The Fog of War", on Robert McNamara and the Vietnam War; and "Standard Operating Procedure", on the Abu Ghraib prison scandal. Morris' groundbreaking work tackles questions of truth, objectivity, and the role of expert knowledge in modern society. His documentaries are renowned for their innovative use of interviews and archival material. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Graduate School of Design.  For decades we have tried to increase high school graduation rates and college completion rates. We've tried to reduce the achievement gaps. We've tried to depolarize our economy and moderate the financial cycles. These and many other public policy efforts have produced disappointing results. This is in part because the policies were based on a partial view of human nature and a simplistic view of human capital. Neuroscientific research over the past few years has pointed toward a richer view, one in which our emotions and unconscious play a far more important role in everyday decision-making. It is time to apply the findings of science to the world of policy, morality and practice. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Graduate School of Design.  America is a nation of between 300 and 400 million people that is still growing and that has needs that are vastly more complex than any of the designs our historical higher education system has the capacity to address. There are intricacy issues, global competitiveness issues, performance issues, fiscal issues, as well as more fundamental issues associated with the types of knowledge we are producing and how we are transferring that knowledge to students in higher learning institutions. With that in mind, and with a very narrow differentiation between U.S. universities, the basic design and structure of a new class of higher education institution will be outlined, and a specific case study of the last eight years at Arizona State University will be detailed. ASU is America's newest, largest and most nimble research university in terms of the speed of its evolution and its impact. This design review and exemplar analysis will be carried out in the context of designing universities for America's complex future. Co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Graduate School of Design.  What happens once democracy has been used up? When it has been hollowed out and emptied of meaning? What happens when each of its institutions has metastasized into something dangerous? What happens now that democracy and the free market have fused into a single predatory organism with a thin, constricted imagination that revolves almost entirely around the idea of maximizing profit? Is it possible to reverse this process? Can something that has mutated go back to being what it used to be? What we need today, for the sake of the survival of this planet, is long-term vision. Can governments whose very survival depends on immediate, extractive, short-term gain provide this? Could it be that democracy, the sacred answer to our short-term hopes and prayers, the protector of our individual freedoms and nurturer of our avaricious dreams, will turn out to be the endgame for the human race? Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the Harvard Humanities Center, the Harvard University Center for the Environment, the South Asia Initiative at Harvard, and the Graduate School of Design, as well as RILES (Resource Institute for Low Entropy Systems).  As the world struggles to recover from the economic crisis of 2008, it is tempting to blame the events on a few greedy bankers who took irrational risks and left the rest of us to foot the bill. In Fault Lines, Rajan argues that serious flaws in the economy are also to blame, and warns that a potentially more devastating crisis awaits us if they are not fixed. He traces the deepening fault lines in a system overly dependent on American consumption to power the world economy and stave off a global downturn; a system where America's thin social safety net has created tremendous political pressure to keep job creation robust, because jobs are the primary provider of health and other benefits; and where the U.S. financial sector, with its skewed incentives, is the critical but unstable link between an overstimulated America and an underconsuming world. In conclusion, heoutlines sensible reforms to ensure a more stable world economy and to restore lasting prosperity. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, the Graduate School of Design, and the South Asia Initiative at Harvard, and the Harvard University Center for the Environment.  How do the new forms of connectivity enabled by the internet affect flows of power in society? Does electronic communication create new forms of self-identification, new political sensibilities, or new avenues of empowerment? Or do old hierarchies get reinforced and familiar divisions, such as those between male and female or right and left, get more firmly entrenched through new routines? How do design choices affect relationships of power, for example, by selecting who should be connected to whom and across what sorts of spaces? Drawing on studies of teenagers and professional designers, cities and the blogosphere, this distinguished panel will lead us on a fascinating journey across today's changing public spheres. They will offer tantalizing glimpses into the democratic imaginations taking shape in cyberspace. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Harvard University Center for the Environment.  Growing certainty that climate change is human-made and will have catastrophic consequences has reshuffled the cards for society and politics across the entire world. But it is a mistake to see climate change as an irreversible path to an apocalyptic future for humankind. Beyond belief and beyond hope, climate change opens up the opportunity to overcome the bounds of national politics and to found a "cosmopolitan realism" in the interests of nation states. Climate change is pure ambivalence. But it is precisely this feature that can be uncovered by the art and practice of the sociologist's methodological skepticism and be publicly turned against the dominant (discourses of?) cynicism and paralysis. In this sense, the sociology of climate change can serve as a heuristic for the productive creativity of uncertain times. Co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Harvard University Center for the Environment.  Many observers have commented on the damage that the current administration has done to science over the past seven years. I will evaluate the effects of this era on the traditional relationship between the scientific enterprise and the federal government, and offer some ideas about what a new administration could do to restore that relationship, increase the confidence of the scientific community in government, and allow the nation to take greater advantage of science and technology. In particular, I will consider measures to strengthen the representation of science in the White House; discuss the possibility of achieving a more predictable, multi-year pattern of funding for science agencies; recommend ways to codify the mechanisms by which the federal government obtains scientific advice and protects the independence of government scientists; and explain why our country should establish stronger roles for science, medicine, and technology in foreign policy. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Harvard University Center for the Environment.  In this lecture drawn from a book of the same title that he is currently completing, William Cronon analyzes key cultural assumptions about humanity and nature that have characterized modern environmental thinking in the United States for the past several decades, in an effort to understand how these have sometimes undermined the effectiveness of environmentalism as a political, social, and cultural movement. His goal will be to try to imagine how environmentalism might be more effective if is followers did a better job of mingling the natural and the cultural in the service of humane values. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Harvard University Center for the Environment.  My purpose in this talk is to examine the declining power of earlier imaginaries of science, nature and reality in sustaining modern democratic categories of civic agency, political participation, and conceptions of apolitical constraints. The change that concerns us is in the idea of popular sovereignty between early to late, or post-modern, democracy. Focusing on the role of fictions in modern political history, I ask what kinds of experience, how many facts, or how much publicly accessible evidence, are needed to lend such a fiction as popular sovereignty the status of believable reality. The historical record suggests that established political fictions are actually sustained by a very small number of "facts." What contributes most heavily to the believability of such fictions is the efficacy with which they match or sustain the normative-epistemological frame of a particular political world. I conclude with a brief examination of the decline of scientific or natural reality as components of post-modern political imaginaries of order, and the consequences of that decline for enacting popular sovereignty in our time. Video of this lecture is located here. Co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Harvard University Center for the Environment. |

||||||